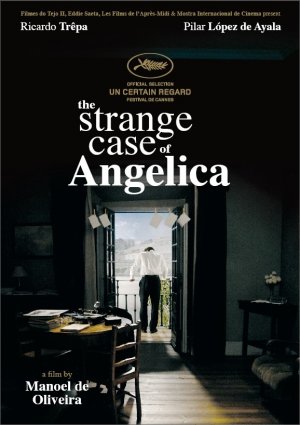

O Estranho Caso de Angélica

Dir.: Manoel de Oliveira

Portugal

2010

97mins

I sure am making things difficult for myself. When I

started Unsequence Cinema sometime last year, the gist of my first post was

that this might be a place where I could simply recommend movies to people. And

here I am merely six entries in, they’re getting longer and longer and in every

one of them there are caveats, conditions, acknowledgements of weakness or

obscurity. I’ve been unable to do what I wanted here; that is, to be so

inspired by my enjoyment of a film that I could recommend it unreservedly,

saying “Just watch it, it’s fantastic.” Instead, the list is varied but small –

Bertolucci, Raoul Walsh, Jean Rollin, Juraj Herz and Bergman – and my acclaim

for the films has always been a little guarded.

Maybe there’s no such thing as having totally unreserved

support for a piece of art. I know this notion is the antithesis to any kind of

proper criticism, but there’s simply no way around the fact that every

suggestion one makes to another person should be appended with the phrase “if

you like that sort of thing”, just as a disclaimer, in the same way that “in my

opinion” might one day be mandatory at the beginning of every sentence that

offers a qualitative judgement. I’d prefer that we all just take this as an

unspoken precondition of everything that escapes our lips, and then perhaps the

time saved by omitting to pre-emptively apologise for believing our own opinions

could be used more productively. We might win back a third of our waking lives

this way. Just think of it.

What am I getting at? Oh yes, The Strange Case of Angelica. This movie has problems. It’s

certainly not helping me to get back on track with my stated aim of using

Unsequence Cinema to recommend, because

it’s the one I have the most reservations about thus far. I’ll get to why, of

course, but I think I ought to first explain why I considered it for an entry.

This film is here primarily because it was written and

directed by a 102-year-old man. As far as I’m aware, that alone makes it

unique. The Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira has been making movies now

for more than eighty years, on and

off, which is of course a totally freakish achievement. Personally, I respect

someone with a long career in the creative arts, and in cinema there’s no one I

know of whose career has been longer. One of the most pervasive clichés within

any kind of social cultural awareness over the last couple of hundred years is

that the best artists peak early and extinguish themselves in a sad collision

of misfortune, personal misadventure and critical misunderstanding. All the

misses. Everybody’s heard it: if you’re a genius, you’ll know it yourself by

22, you’ll be dead at 27, and the rest of the world might catch up in time for

some distant relative you’ve never met to live comfortably off your royalties.

This model is cynical, and it fosters such utterly wrong-headed romantic

notions that it can only be poisonous to the will. And so when I discover

someone with a long and successful creative career, perhaps someone who is peaking in their seventies or eighties,

it genuinely lifts my spirits. The very idea, then, that a centenarian is

capable of helming a movie (although admittedly this is a low-key drama, not Apocalypse Now) will attract me by its

novelty; its mere existence is a massive “fuck you” to those who would

perpetuate the personality cult of the Art Martyr. And beyond even that,

Oliveira’s later movies offer us the chance to ponder the changes that old age

brings to the imagination – that

quality so often held to be the purest reserve of children. When an old man

sits down to create an original story, what have become the core concerns of

his work? What has he abandoned or resolved along the way? In developments that

may well be the result of declining physical dexterity as well as a natural

distillation of themes and ideas, many older artists have simplified their

output. For some reason, I’m thinking here of the uncluttered canvases of

Georgia O’Keeffe from the mid-1960s onward, or the raw and lumbering final recordings of the delta blues guitarist Son House over the turn of the 1970s.

Something about old age has forced them to reduce their art down to its skeletal

form. In the cases of both O’Keeffe and House, the cause was indeed physical

degeneration. I’m not saying this is the only way to go, and incidentally

Oliveira is remarkably healthy, but I am

saying that perhaps being grand is a young man’s gesture.

What I’m driving at here is that The Strange Case of Angelica is most assuredly not a grand

gesture, and it really does feel like a film made by a very old man. It is

quiet, considered, quaintly attractive to the eye – all made possible by the

over-all simplicity of the film. But in this case both the positive and

negative connotations of the word ‘simple’ are equally applicable. What The Strange Case of Angelica gains by

its modestly charming aesthetic choices and tranquil pace, it almost loses by

its unconvincing script and shallow gestures towards symbolism that turn out to

be very woolly indeed. And because of how much I wanted to love a movie made by

a 102-year-old man, it’s damn near heartbreaking that it turns out to be a

handsome but ultimately meaningless experience.

But forget Oliveira’s age and experience for a minute. The

opening twenty minutes is very strong indeed, and so even within the film’s own

context it’s disappointing that Angelica doesn’t

go on as well as it starts. The main character is Isaac, a solitary photographer

boarding with a superstitious old landlady somewhere in Portugal. He is

called upon late one night in an emergency: the daughter of a wealthy family

has died and they want her photographed, one last time, looking beautiful and at

peace. He arrives and the house is full of mourners, and a nun who is not well inclined

towards the young Jewish man in their midst, but needs must – the dead Angelica

is waiting on a chaise longue, and she most certainly lives up to her name.

When Isaac looks through the viewfinder, the woman opens her eyes. Naturally he

is spooked, and finishes the job quickly before rushing out of the house.

This is the beginning of Isaac’s doomed obsession with the

dead young woman. It’s also the middle of it, and very nearly the end too. I’m

being facetious, but really there’s no development of this idea beyond the

initially striking opening reel. When she opens her eyes for the first time,

the audience truly feels it. Later, in a turn that will challenge the

commitment of some viewers despite the modest running time, she arrives on

Isaac’s balcony as a ghostly apparition and the two of them float dreamily (and

horizontally) through the night. The

Strange Case of Angelica, then, verges on a sort of weird Gothic romance,

and this tone is amply served by the slow and slightly overwrought performances,

and beautifully framed interior scenes.

So far there’s nothing stopping the film from being a nicely low-key success, but the number one problem is the script. It is just not a good script at all. At one point Isaac goes out with his camera to photograph some agricultural workers manually tilling the fields. He then pegs these developing prints – angry-looking rustic men with hoes – alongside the prints of the dead Angelica, who occasionally comes to life again within the frames. When asked why he has been photographing such an outmoded practice as manual agriculture work, he says something like “I prefer the old ways to the new”. I may be paraphrasing there, but crucially I’m not simplifying – the film really does offer nothing more than that statement. I’m crying out for this to be developed a little, or explained: if these images stand for Isaac’s growing isolation and distaste for the modern world, what’s the significance of their juxtaposition with the Angelica photographs? Am I not trying hard enough here? There’s no real link, just the pairing up of two things it’s possible for a wistful and detached arthouse film protagonist to be wistful and detached about. And later, there’s a truly bizarre lunch conversation about engineering, matter and anti-matter that comes out of absolutely nowhere and offers no further insight into Isaac’s predicament, either as a direct metaphor or as a way of establishing an ontological or epistemological world beyond/behind the modest little story at hand. Perhaps that’s not what the conversation is there for, but I’ve not come into the film expecting these questions to be addressed, I’m only responding to what’s there, what’s being established by the film itself. And unfortunately, the audience is asked only to accept that Angelica reveals herself to Isaac in the pictures and in ghostly form, and that he falls in love with her to the brink of a kind of mad despondency. How the other elements of the film relate to its central plot frankly escapes me. Reference points seem barely sketched in. It’s rare for me to say this of an arthouse film, but I think it needs to be longer. An extremely well-shot if incongruous fifteen minute discussion about anti-matter might make a beguiling centrepiece in a movie willing to put more flesh on its bones, but in The Strange Case of Angelica it takes up one sixth of the running time, and establishes nothing except that the landlady is a simple woman who doesn’t understand science, and Isaac is a “strange man”.

This is the scene that proved to be most divisive for the

users of the now-ubiquitous IMDb; there are arguments on the message boards

about it. The usual stuff, you know: one side with a predilection to bait arthouse

fans (I have no idea how they even get to see

movies like this if that’s how they feel), and the other side who are

completely sold on the auteur credentials of the filmmaker or are unwilling to

challenge something they’ve become emotionally attached to. I more often fall

into the latter camp (and that’s why I banished myself from the IMDb boards a

long time ago), but in this instance I get both sides. The fact is, The Strange Case of Angelica is a lovely

film in many ways – it’s made with the assurance of someone who has long known

how to stage, light and edit his films to get the precise tone and pace he

wants – but as a result it’s the photography that will stay in your mind after

you see it. The ideas won’t, because there are few. In these screenshots, I

think it’s possible to detect the tone of the performances and the patience of

each scene, and that in itself is the marker of some cinematic success.

I don’t want to leave Manoel de Oliveira on a bad note

because it’s not a bad film, it’s just a strangely empty one, so I fully intend

to watch another of his films very soon, a very old one, Aniki-Bóbó. This is his first feature length fiction, released in

1942, and if my memory serves me it was featured in Mark Cousins’ stunning The Story of Film last year. That was

the real reason I found myself watching Angelica:

of course I wanted to see the work of a centenarian filmmaker, but I also

wanted the opportunity to see something he made in his early thirties, which in

cinematic terms is practically an ice age ago. I may report back.